Decorative painting – or mural painting, as it came to be known – was experiencing something of a resurgence in the early 1900s. The BSR, influenced in part by the Slade School of Art, was a significant driver of this development, despite the fact that the Fine Arts were never the main priority of the School. It suited its subsidiary mission, secondary though it was to advance the discipline of archaeology, which was to support the creation of aesthetically pleasing public spaces. This was achieved through the three initial strands of the Rome scholarships: architecture, sculpture, and decorative painting.

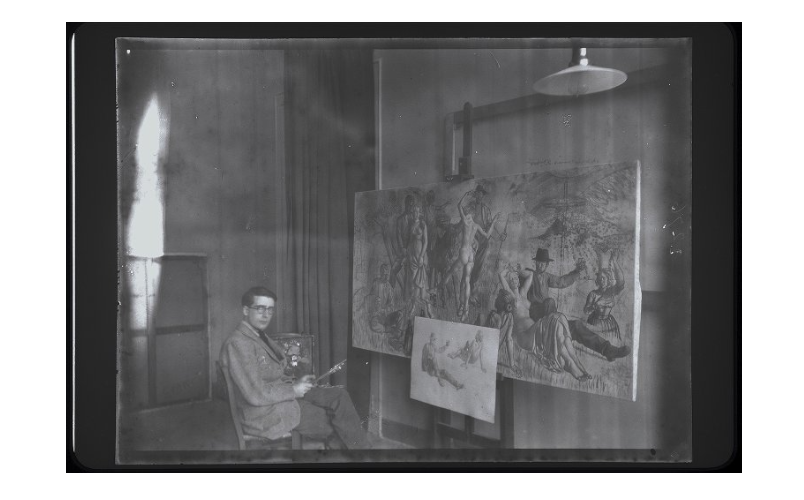

Artists, though left largely to their own devices with regards to their learning, were placed in Rome with the expectation that they would absorb the classical traditions that the space embodied. The artists were not taught, but rather learnt, studying the likes of Piero della Francesca (c.1415-1492), and meeting the School’s challenging re-enrolment requirements. It was the intention of the academy that the artists would, after the conclusion of their studies, be available for public commissions.

It was this renaissance tradition that the British academy, not to be outdone by the French, was trying to reinvent. Eugénie Sellers Strong (1860-1943),Assistant Director of the BSR until 1925, was an outspoken advocate for the documentation of murals extant across Britain, lest the art be forgotten. She likely had in mind, too, the legacy of the scholars under her care in Rome: Colin Gill (1892-1940), J. M. Benson, Winifred Knights (1899-1947), Tom Monnington (1902-1976), A. K. Lawrence (1893-1975), R. Lyon (1894-1978), and Edward I. Halliday (1902-1984). Later Rome Scholars in painting of this period include Glyn O. Jones (1906-1984) in 1926, R. C. Brill (1902-1974) in 1927, Alan Sorrell (1904-1974) in 1928 and H. A. Finney (1905-1991) in 1929.

Unlike other artworks, murals were especially at risk of being destroyed, painted over, or moved, given their stubborn adherence to the walls of public buildings. If the tastes of the time changed, or the art was recognised as being overly political, then the ephemerality of the artist’s work would be soon realised. The main irony here, was that these works were often the artist’s most ambitious, and at the same time were the most likely to be written out of the accounts of their lives. Another pressure came from restrictions on artistic expression, given that the art had to appeal to a particular interest, especially if it adorned the walls of a parliamentary building, and be as inoffensive as possible.

The most significant failure of the BSR’s mission to educate its artists in the classical tradition, however, was that, while the artists were busily emulating the frescoes of Piero, the world around them changed. There is something romantic in this tragedy. While the Rome Scholars spent time in Rome, in a bubble of their own and shielded from the outside world, or in Anticoli Corrado, a picturesque hillside village where they could admire the elegant simplicity of ‘primitive’ Tuscan life, the world around them became more war torn, and more fascist. This is not to say that the School was unaffected by these influences. Colin Gill left the School in 1915 to join the war effort, and the School closed periodically from 1935 under pressure from Mussolini, caught up as it was in the grander disputes between Italy and Britain. The influence of this tension between the needs of the School and the broader diplomatic goals of the British state were felt when the British Ambassador in Italy vetoed the appointment of Aubrey Waterfield (1902-1944), an outspoken anti-fascist, as director in 1932. This had broader implications for the School, for Waterfield was recommended for his skill as a watercolourist, and was put forward in response to the observation that archaeologists had for too long remained the dominant force within the BSR.

This shifting political landscape was accompanied by the shifting cultural landscape. The popularity of abstraction left the Rome Scholars in decorative and mural painting torn. Sweeping electrification, mechanisation, and the eventual advent of the nuclear world undoubtedly had its influences on the world of art. The School’s committee were well aware of the impact that “extreme ‘abstract’” ideas could have on the students’ views; the appeal of an artist as director in 1932 was that they might help students steer themselves around these ideas, “which”, according to Sir William Rothenstein, “settle like microbes in the students’ brains”.

Shifting cultural tastes, with the push of traditionalism and the pull of abstractionism, had its effect on the careers of the Rome Scholars. It is perhaps no surprise that their earlier works seemed to be their most impactful: Colin Gill’s Allegro, produced in 1927, was his most celebrated, while Winifred Knights’ legacy has been defined most by The Deluge, the piece she produced to win the Rome Scholarship. Tom Monnington’s career perhaps best demonstrates this push and pull, for he was able to shift with the times, allowing himself to be influenced by geometry and wartime experience in a way that others were not, Gill’s untimely death notwithstanding.

The confluence of these forces – the traditional against the abstract, the shifting politics against the artistic bubble – means that we are left with a collection of works that have come to define British art of the interwar period. The murals and canvas paintings these artists produced speak to the changes of the time, demonstrate their talents, and offer parallels by which we may understand our own experiences. The Rome Scholars of the 1910s and 1920s were not, after all, the first to be caught amidst these forces, nor have they been the last.

Where would you like to visit next? Who would you like to meet?

Sources and Further Reading

The Marriage at Cana (1923) by Winifred Knights. Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/39515.

Liss, P. Llewelyn, S. Et al. (2013). British Murals & Decorative Painting 1920 – 1960. Bristol: Samson & Co.

Liss, P. Llewelyn, S. Et al. (2013). British Murals & Decorative Painting 1910 – 1970. Bristol: Samson & Co.

Powers, A. (1985). British Artists in Italy 1920–1980. Kent: Canterbury College of Art.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (Ed). (2001). The British School at Rome: One Hundred Years. Rome: BSR.

Wiseman, T.P. (1990). A Short History of the British School at Rome. Rome: BSR.

For a full bibliography and further reading, see here.