Alfred Hardiman (1891-1949) was the 1920 winner of the Rome Prize for Sculpture and resident at the BSR for four years. One of a new wave of artists emerging from British artisanal communities, he was born the son of a master silversmith in Highbury, London in 1891. He studied and worked as an engineering draftsman before coming to artistic study at the Royal College of Art and the Royal Academy. Whilst a student, Hardiman came into contact with the sculptures of Augustes Rodin and Ivan Meštrović, which influenced his work throughout the 1920s. Whilst studying, he also met contemporaries Charles Wheeler and his predecessors as Rome Sculpture scholars, Gilbert Ledward and Charles Sargeant Jagger. He would practice his art by using other scholars as models. Amongst these was fellow Rome Scholar and painter, Winifred Knights.

Hardiman served as a draughtsman in Royal Naval Reserve in the First World War and was elected a member of the British Society of Sculptors before being awarded the Rome Prize. He was a Rome Scholar from 1920 to 1923, staying an extra year at the school with his wife, Violet Hardiman (née White) who worked as Bursar and Secretary for the School. As the BSR administration did not permit married couples to cohabit at the School until later in the 1920s, the Hardimans had to live off premises.

Hardiman’s practice was strongly influenced by his time in Italy where he produced several of his most notable works in the BSR studios, including busts of his fellow Rome scholar Winifred Knights (1899-1947) and BSR director Thomas Ashby (1874-1931). He was particularly struck by the classical art he was exposed to in Italy and the scholarship of the BSR community. Several relics of Etruscan art, the culture of the Italian peninsular prior to the Roman empire, had only recently been re-discovered in Rome and were exhibited at the nearby Villa Giulia. The BSR’s Eugénie Sellers Strong (1860-1943) had studied and lectured on the period. One such work was the Apollo of Veii (c.510 BC) excavated by Guilio Giglioli in 1916 which had also had an influence on Hardiman’s contemporary, Italian sculptor Arturo Martini (1889-1947).

Another clear influence on Hardiman’s sculptures was the Charioteer (c.475-470 BC) from Delphi. Hardiman was one of several sculptors and artists of the period, such as Martini and Ledward, who were incorporating elements of classicism into their works, aligning with some of the primitivist modernist trends of the period and the ‘return to order’ after the violent disruption of the First World War. Avant Garde cultural movements such as Futurism and Novecento Italiano had grown up in Italy in the previous years. While artists like Hardiman brought some modernist elements into his approach, the traditionalism of the Rome Prize may have curbed too much deviation away from classicism. Valerie Holman describes Hardiman and other sculptors of the time as having an admiration for the “uncorrupted purity of form” of Greek and Roman art, an aesthetic tendency that cannot be separated from the context of the Fascist political movements emerging after the First World War in Italy and Europe at this time.

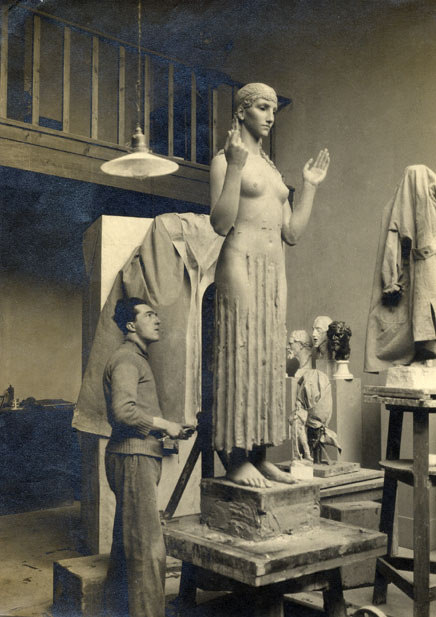

Both classical and modernist influences can be seen in the key work Hardiman made in Rome, Peace (Piccadilly Gardens, 1926), which now stands as the sculptor’s own memorial in St James’s garden in Piccadilly, London. Several versions of this two-metre high statue were made whilst at the BSR, but the final version was not cast until 1926 due to the cost of materials. Numerous images of this work in progress can be found in the BSR archive. The sculptures Hardiman made in Rome mark a period where he was not yet constrained by the requirements of the later public commissions which he was to become known for. Hardiman also became a member of the Faculty of Sculpture and went on to collaborate with the architects associated with the School.

After his period in Rome, Hardiman worked alongside architects on public works and building projects in Britain which remain standing today. One of his statues was extremely controversial. In making the Haig memorial, Hardiman struggled to balance the swings of opinion and public taste, the requirements of Haig’s widow and supporter, with his own aesthetic and practical intent. Other more striking successes can be found at Norwich County Hall, where he worked with fellow Rome Architecture scholar S. R. Pierce (1896–1966), and in several other cities across the UK. During the blitz in the Second World War, Hardiman’s studio and home took a direct hit from a bomb. The buildings, his possessions, materials and many original pieces, models and casts were completely destroyed and he struggled to receive full compensation for his losses. He died of cancer in 1949.

Where would you like to go next? Who would you like to meet?

Sources and Further Reading

Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, 1851 – 1951. https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/ Henry Moore Institute.

Holman, V (2015). Alfred Hardiman, RA, and the Vicissitudes of Public Sculpture in Mid-twentieth-century Britain in Sculpture Journal, January 2015, 24(3): 351-373.

For a full bibliography and further reading, see here.