by Raffaella Bucolo, BSR Research Fellow

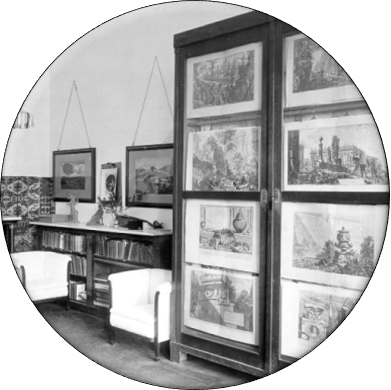

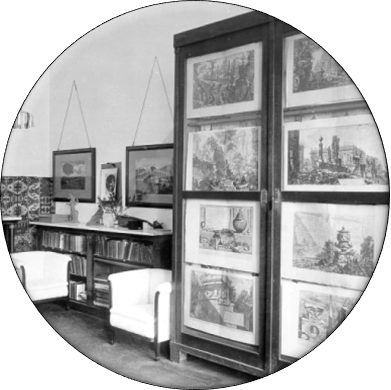

Cesare Faraglia, who was born in Rome on the 10th October 1865, was a highly respected photographer who worked with archaeologists and art historians during the first half of the twentieth century. Almost nothing is known about of the early years of Faraglia’s activity as a photographer: his work began to be published in art magazines from 1905. He must already have been well-known before that date, however, since eminent scholars and collectors, such as Ludwig Pollak and Giovanni Barracco, chose him to photograph their art works and private rooms. A photograph of Pollak’s living room in Palazzo Odescalchi was taken by Faraglia between 1928 and 1943.

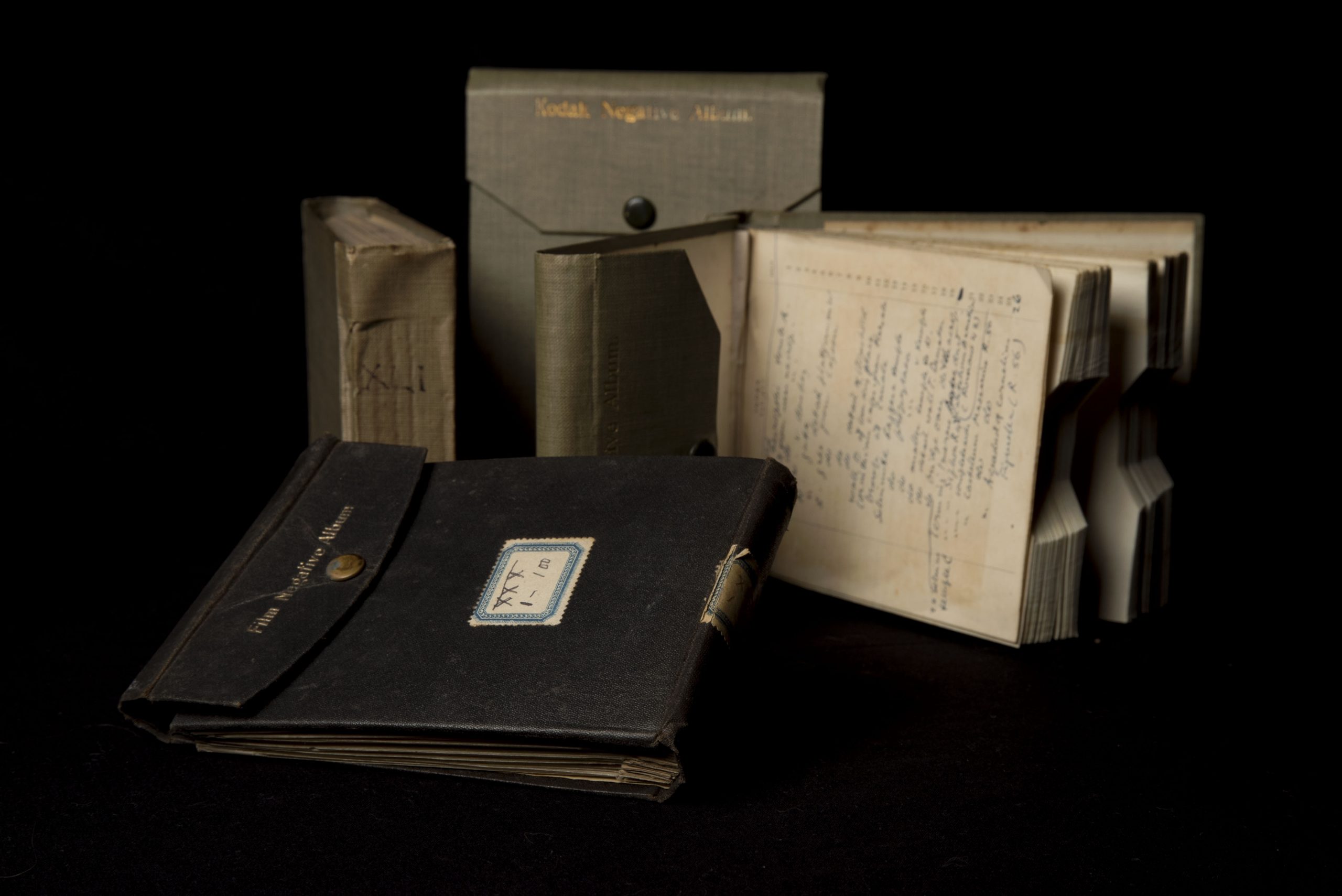

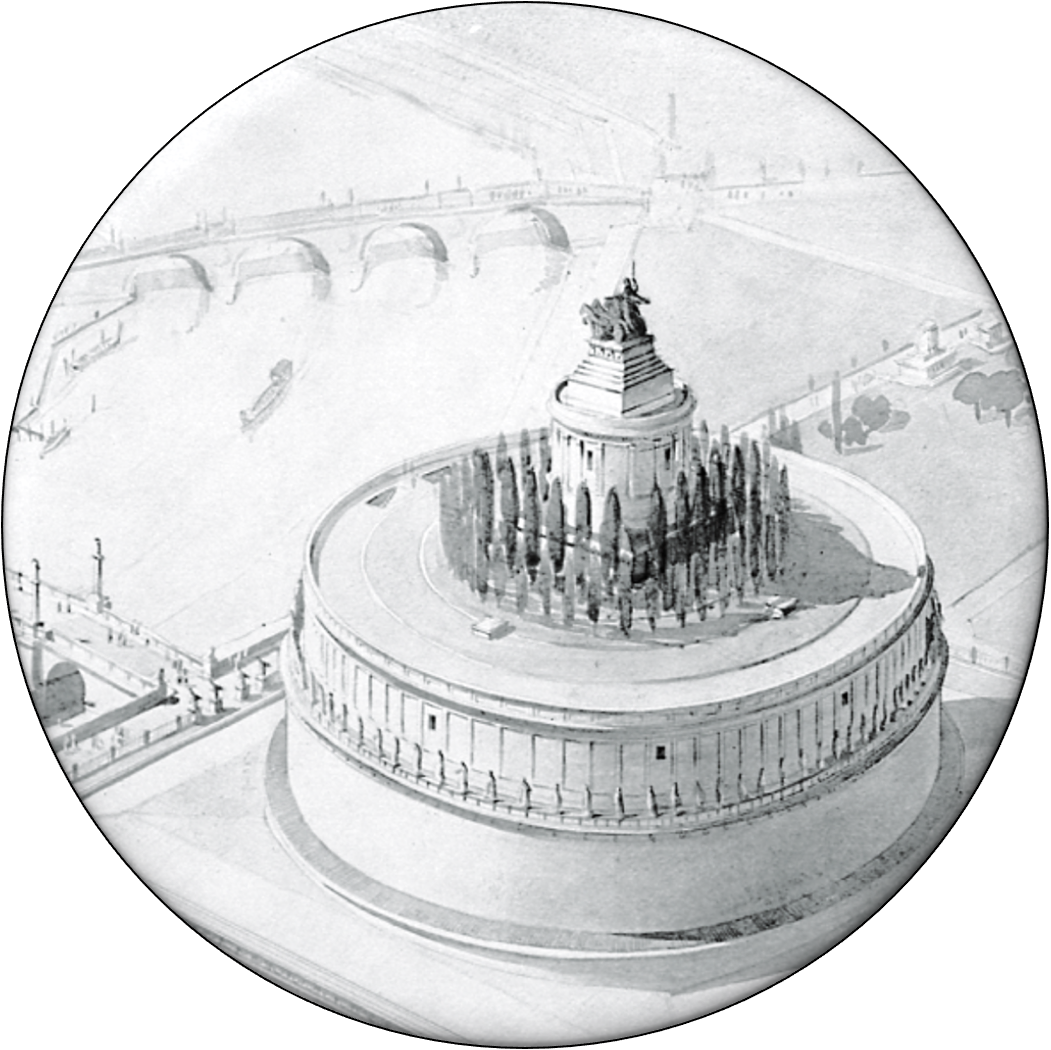

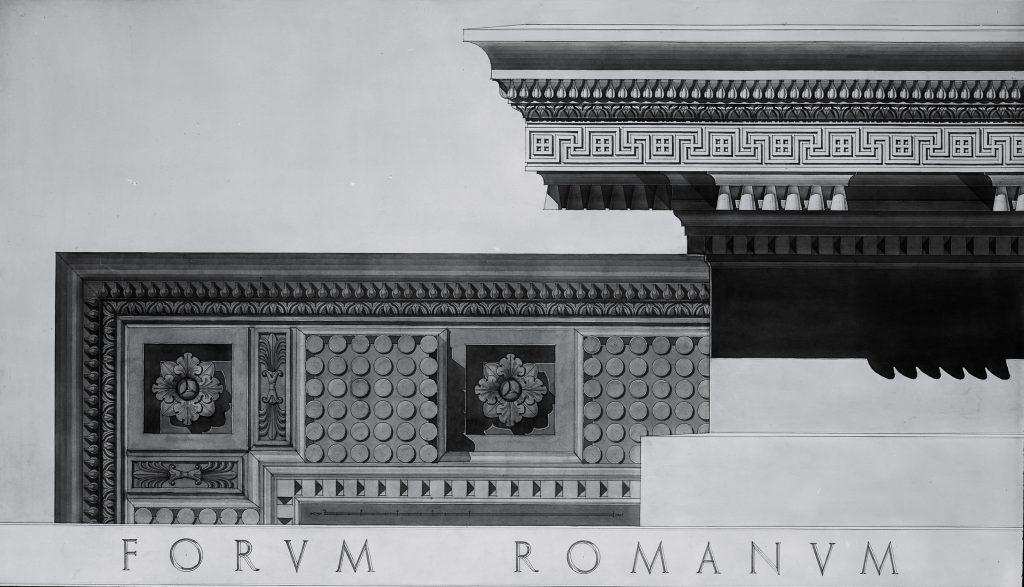

The true launch pad for Faraglia’s career was the close collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute for which he worked as a freelance photographer from the end of the nineteenth century, and after 1906 in a much closer collaboration. In 1906 he was commissioned to photograph the antiquities at the Vatican Museum, a considerable task that took him almost forty years to complete. After 1910 and until the end of his life, Faraglia’s photographs filled the pages of scientific journals, catalogues, art books and works on architecture and archaeology.Faraglia’s photographic studio was located at 14 via Messina 14: he referred to himself as the photographer of “Institutes and Archaeological Schools”, a self-definition that he reproduced on his stamps, letterheads and also in advertisements.

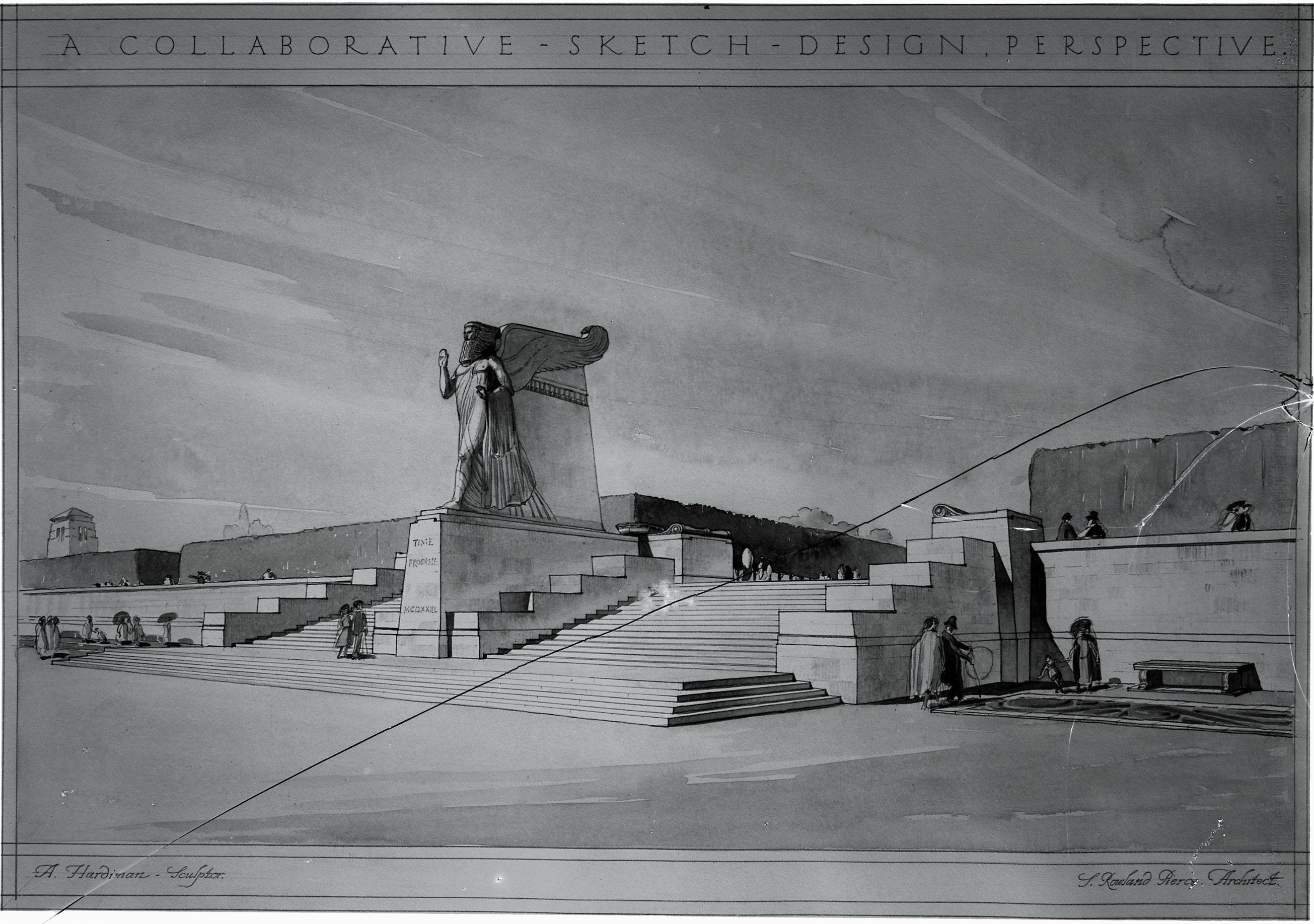

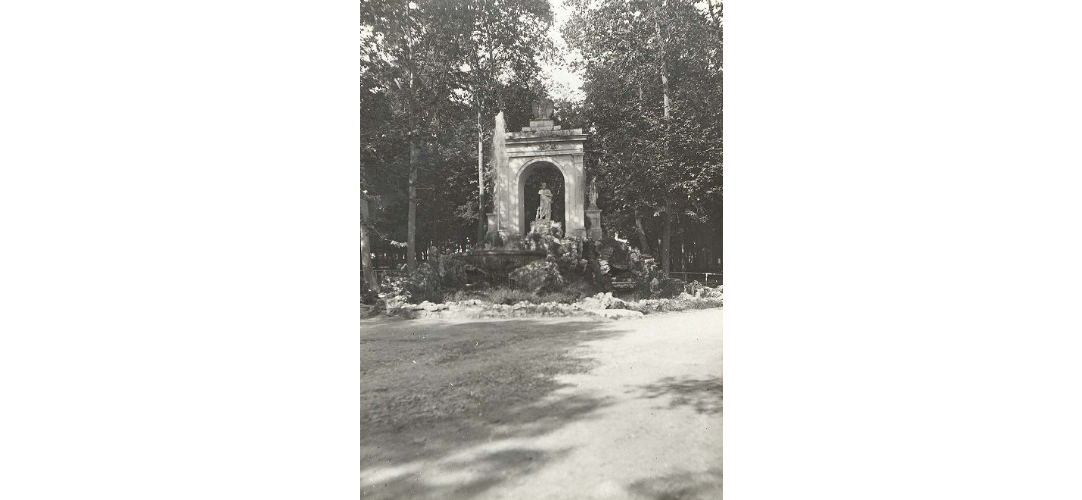

Cesare Faraglia worked for many of the foreign research Institutes in Rome, which commissioned his photographs of important monuments such as the Arch of Septimius Severus and the Arch of Constantine, which he was able to do thanks to the construction of bespoke scaffolding. Proof of Faraglia’s professional renown can be seen by the fact that he was invited by the “Governatorato di Roma” to document, together with other important photographers, the largescale demolition of the historic city centre that took place between 1924 and 1940.

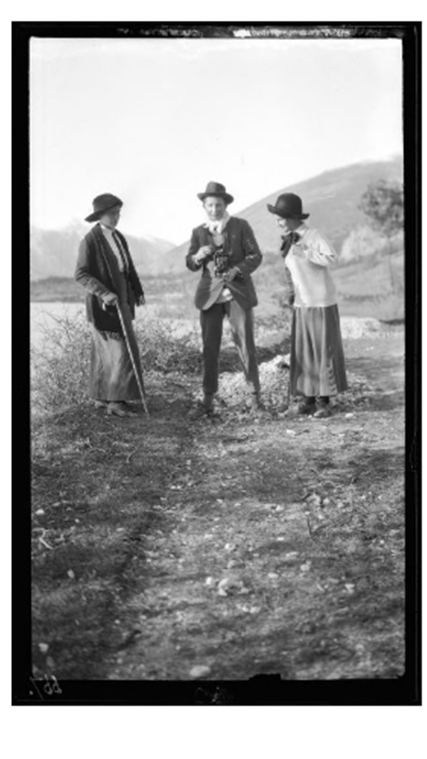

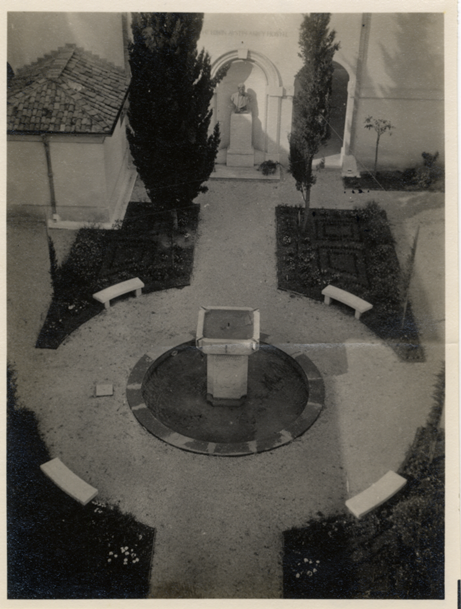

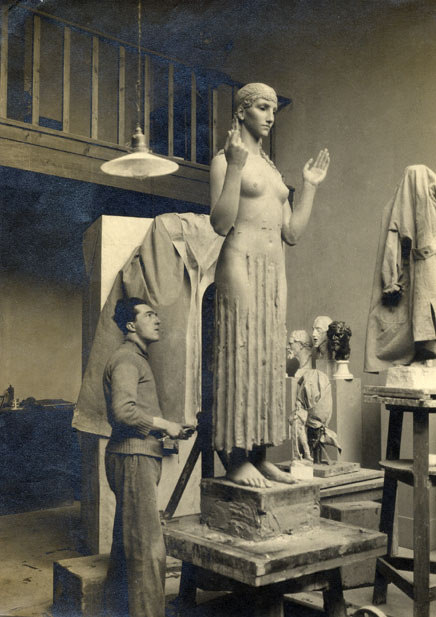

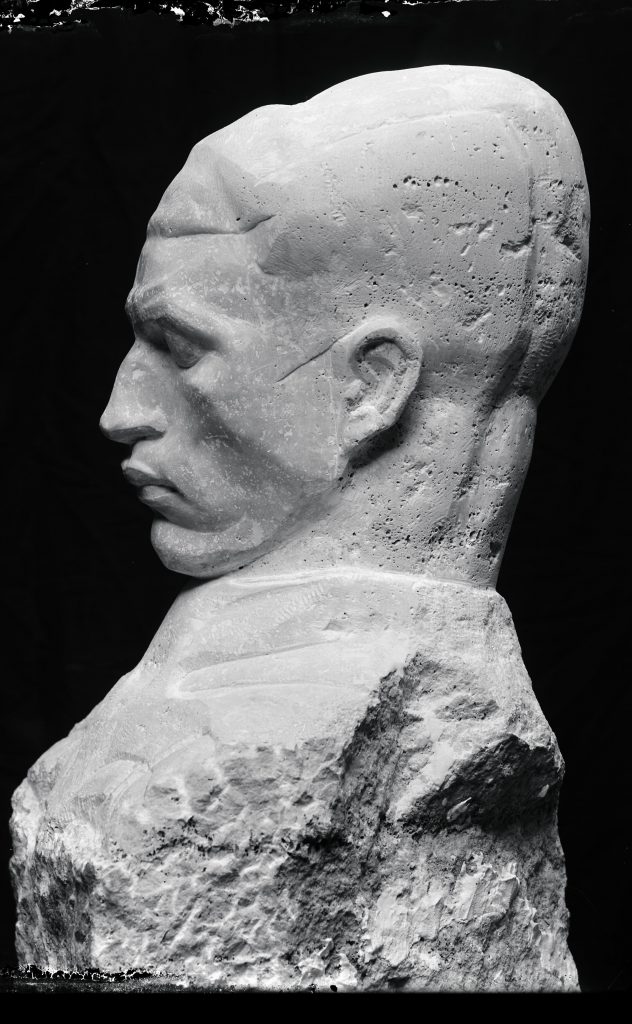

Faraglia collaborated for many years with the British School at Rome and his works are kept in various parts of the Photographic Archive. He worked side by side with eminent scholars of the British School and was also the author of the figures published in Henry Stuart Jones’ seminal volumes about the marble antiquities in the collections of the Capitoline Museums (A catalogue of the ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome. The sculptures of the Museo Capitolino, Oxford 1912; The sculptures of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Oxford 1926). Faraglia was also the author of a number of photographs of the British School’s interiors, as well as of the studios and artworks of the fellows in Fine Arts, who are sometimes immortalized alongside their artistic works in the photographs.

Cesare Faraglia died in Rome at the age of eighty-one: his significant contribution to of the field of fine arts is recorded on his tombstone.

Sources and Further Reading

Becchetti, P. (1983) La fotografia a Roma dalle origini al 1915, Rome, p. 305.

Bockmann, R. (2017) Cesare Faraglia (ca. 1870–1950). Ritratto femminile, detto Busto Fonseca, 1912, in: M. F. Bonetti, C. Marsicola (ed.), Alfabeto fotografico romano. Collezioni e archivi fotografici di istituzioni culturali in Roma (Ausstellungskatalog Rom), Pomezia/Rome 2017, p. 296, Kat. B4.

Bucolo R. (2015), Margarete Gütschow. Biografia e studi di un’archeologa, Supplementi e Monografie della Rivista Archeologia Classica, 13-n.s. 10, Rome, pp. 52, 160-161.

Bucolo R. (2016), Cesare Faraglia. Fotografo degli Istituti e Scuole di Archeologia.

Poster for the Conference: Archeologia e documentazione fotografica d’archivio dal dagherrotipo all’avvento della fotografia digitale, (Aquileia, 28-29 April 2016)

Di Giammaria P. (2015), Gli albori della raccolta fotografica dei Musei Vaticani e la Fototeca oggi, tra conservazione e innovazione B. Fabjan (ed.), Immagini e memoria, Gli Archivi fotografici di Istituzioni culturali della città di Roma, Atti del convegno (Roma, Palazzo Barberini, 3–4 Dezember 2012), Rome, pp.157-168.

Di Pinto R. (2009), Attorno ai Patti Lateranensi. Indagine sulla formazione dell’Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Vaticani, in: A. Paolucci, C. Pantanella (edd.), I Musei Vaticani nell’80° Anniversario della firma dei Patti Lateranensi, 1929-2009, Florence, pp. 401-425.

Margiotta A. (2007), Fotografare le demolizioni, in R. Leone, A. Margiotta, F. Betti, A. M. D’Amelio (edd.), Via dell’Impero. Demolizioni e scavi. Fotografie 1930-1943, Rome, pp. 13-19.

Rossini O. (2018), Ludwig Pollak. La vita e le opere, in: O. Rossini (ed.), Ludwig Pollak. Archeologo e mercante d’arte. Praga 1868-Auschwitz 1943. Gli anni d’oro del collezionismo internazionale da Giovanni Barracco a Sigmund Freud, Rome, pp. 14-35.

Schallert, Röll 2014: Schallert, R., Röll, J. (2014), La Fototeca della Bibliotheca Hertziana (Istituto Max Planck per la Storia dell’Arte), in: B. Fabjan (ed.), Immagini e memoria, Gli Archivi fotografici di Istituzioni culturali della città di Roma, Atti del convegno (Roma, Palazzo Barberini, 3–4 Dezember 2012), Rome, pp. 169-182.

See also Cesare Faraglia | Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte (biblhertz.it)

For a full bibliography and further reading, see here.