The Rome Prize for Sculpture was established as part of the new Fine Arts Faculty in 1913. Its inception was part of a broader movement to create a new generation of British sculptors who, influenced by the classical and traditional sculpture of Rome, could contribute monumental works to public spaces in Britain. In T. P. Wiseman’s words, the stipulations to entrants in sculpture “reflected rigid conditions of classical study still firmly established in the art schools in Britain at the time”, with entrants asked to submit models, drawings and designs of set subjects. These included nude figures, drapery, hands, feet and architectural features to set sizes. In the final round of the competition entrants had to submit “a design for a Figure group or Relief (as determined by the Faculty of Sculpture) for a given purpose and to a given scale”.

The British sculptors awarded the Rome Prize in the early period of the BSR include Gilbert Ledward (1888–1960) in 1913 and C. S. Jagger (1885–1934) in 1914, both of whom left the school in order to fight in the First World War. Ledward joined the army and served in Italy, while Jagger never completed his Rome Scholarship after joining the Artists’ Rifles in 1914. Both went on to become some of Britain’s most notable sculptors of memorials to war.

After the war, Alfred F. Hardiman (1891–1949) had a productive residency at the School. He was followed by J. A. Woodford (1893–1976) in 1922, David Evans (1893–1959) in 1923 and John R. Skeaping (1901–80) in 1924. Skeaping was joined by Barbara Hepworth (1903–75), who lived at the BSR for a period with him over 1925–6. Later in this period, scholars included E. Jacot in 1925, H. Wilson Parker in 1927, C. Brown in 1928 and J. F. Kavanagh in 1930. Other sculptors such as Henry Moore and Hepworth visited the school as traveling scholars. Several of these sculptors came from artisanal, metalworking and working-class backgrounds, a result of the emerging focus on design in technical training in British educational institutes.

As was envisioned at the founding of the prize, the art, culture and environment of Rome, as well as the proximity of practitioners of architecture, archaeology and painting, were deeply influential on the sculpture scholars. The sheer abundance of Rome’s classical, Renaissance, Baroque and modern art, as well as the topography and archaeological findings that were being unearthed in surrounding regions at the time, all formed part of a rich nexus of artistic influence on the Rome Scholars.

Despite the traditionalist strictures of the prize and the School, several sculptors in the 1920s used their time in Rome to develop new ideas and techniques; many were influenced by the modernist trends coming out of France and Germany, as well as the recent interest in African and Oceanic sculpture. Henry Moore’s time in Italy and briefly at the BSR in 1924 greatly shaped his later work. And Barbara Hepworth met her first husband, fellow sculptor John Skeaping, whilst he was a scholar at the BSR (1924–6). Hepworth herself had been a runner-up for the Rome Prize which Skeaping had won and was in Italy on a traveling scholarship. They married in Florence and she lived with him at the school from 1925 until 1926, when they returned to Britain due to Skeaping’s ill health.

Whilst in Rome, Hepworth and Skeaping learnt marble carving from Italian master carver, Giovanni Ardini. Ardini’s remark that “marble changes colour under different people’s hands” was particularly striking to Hepworth, and she wrote that Ardini’s mentorship “opened up a new vista for me of the quality of form, light, and colour contained in the Mediterranean conception of carving”.

Skeaping was later known as a proponent of direct carving whereby works are shaped from the beginning out of the final material – usually stone or wood – thus emerging with the nature of that material itself. He was later known for his figures of animals and the designer of the fountain in the centre of the BSR courtyard, whose reliefs onto travertine depict the deer which went on to feature again in his later animal forms.

Sculptural practice took place in the BSR’s studios. Although materials were less costly in Italy than in Britain, the stipend for artists at the BSR was not substantial. Some sculptors such as Alfred Hardiman struggled to purchase the materials necessary to finally cast their works in expensive materials such as bronze. Several of the BSR sculptors worked alongside architects to realise monumental works, as envisioned by the School’s strategic aims. Hardiman, for example, went on to produce sculptures with Rome Architecture scholar S. R. Pierce at Norwich County Hall.

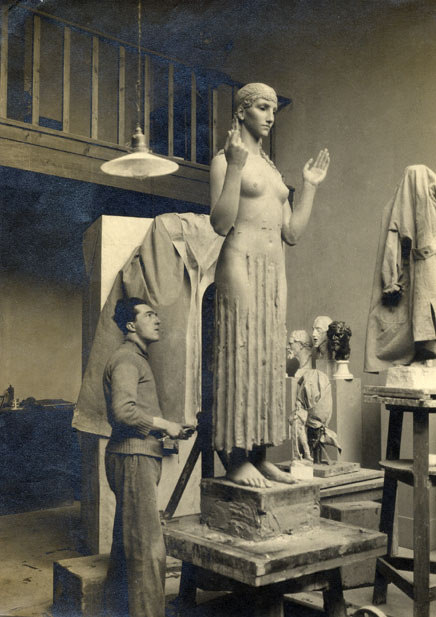

In the BSR Archive you can find correspondence between the scholars and faculty as well as several photographs of some of the Rome sculptors at work alongside images of the works they made and were inspired by.

Each of these sculptors received a Rome Prize medal, several of which are held in the BSR archives.

Where would you like to go next? Who would you like to meet?

Sources

Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, 1851-1951. Henry Moore Institute.

Holman, V (2015). Alfred Hardiman, RA, and the Vicissitudes of Public Sculpture in Mid-twentieth-century Britain in Sculpture Journal, January 2015, 24(3):351-373.

Hepworth, B. (1946). ‘Approach to Sculpture’, The Studio, London, October 1946, vol. CXXXII, no. 643, p. 97.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (Ed). (2001). The British School at Rome: One Hundred Years. Rome: BSR.

For a full bibliography and further reading, see here.