The Borghese gardens, known now as the Villa Borghese, are only a short walk away from the BSR. They are an historic site, converted from a vineyard in the seventeenth century by Scipione Borghese. In the nineteenth century they were redesigned as a landscape garden, inspired by the English style. Despite this influence, they far surpassed the English gardens in the eyes of some commentators.

The American author Nathaniel Hawthorne describes the Borghese gardens in his novel, The Marble Faun (1860). The gardens, according to Hawthorne, had a “sylvan character”; “the scenery amid which the youth now strayed was such as arrays itself in the imagination when we read the beautiful old myths, and fancy a brighter sky, a softer turf, a more picturesque arrangement of venerable trees, than we find in the rude and untrained landscapes of the Western world. The ilex-tress, so ancient and time-honored were they, seemed to have lived for ages undisturbed, and to feel no dread of profanation by the axe any more than overthrow by the thunder-stroke”.

The gardens were filled with trees and flowers that seemed to almost overwhelm the senses. As Hawthorne writes, “in other portions of the grounds the stone-pines lifted their dense clump of branches upon a slender length of stem, so high that they looked like green islands in the air … there were avenues of cypress, resembling dark flames of huge funeral candles, which spread dusk and twilight round about them instead of cheerful radiance”. There were “anemones of wondrous size, both white and rose-colored, and violets that betrayed themselves by their rich fragrances, even if their blue eyes failed to meet your own.” Thus, Hawthorne concludes, “these wooded and flowery lawns are more beautiful than the finest of English park-scenery, more touching, more impressive”.

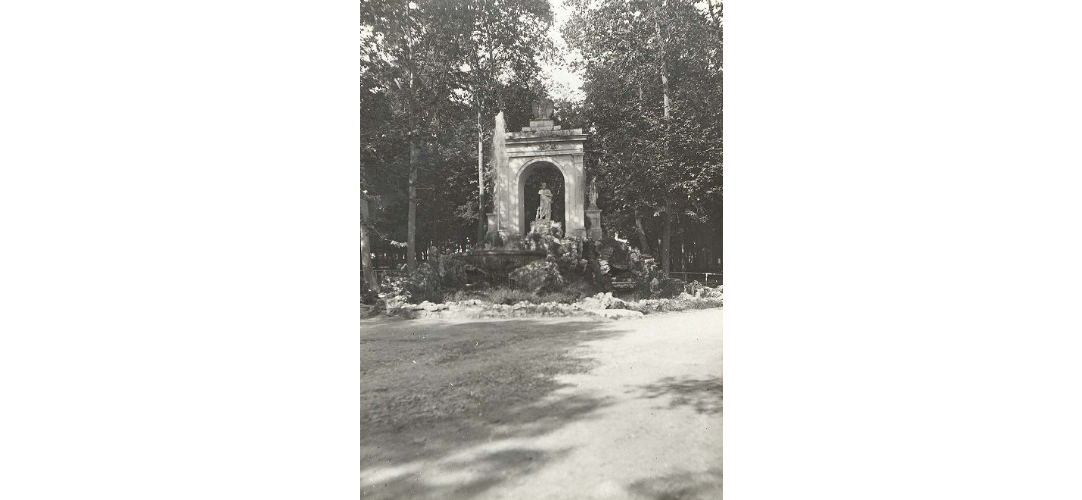

It is “an ideal landscape, a woodland scene that seems to have been projected out of the poet’s mind.” There are fountains, and statues of Roman figures: “The result of all is a scene, pensive, lovely, dream-like, enjoyable and sad, such as is to be found nowhere save in these princely villa-residences in the neighborhood of Rome; a scene that must have required generations and ages, during which growth, decay, and man’s intelligence wrought kindly together, to render it so gently wild as we behold it now.”

They were open informally to the public since their inception, with Hawthorne writing that the gardens offer “a seclusion, but seldom a solitude; for priest, noble, and populace, stranger and native, all who breathe Roman air, find free admission, and come hither to taste the languid enjoyment of the daydream that they call life.” This was formalised in 1903 when the gardens were bought by the commune of Rome. They did not lose their ability to inspire the arts. In 1924, Ottorino Respighi finished the Pini di Roma, a four-movement orchestral piece, arranged as a symphonic poem (a piece of music written to evoke the content of a poem). This piece depicted the pine trees of Rome; the first movement was centred on the pines of the Borghese gardens. The light, high tempo opening movement portrayed children playing loudly by the pines, dancing in circles and pretending to be soldiers.

It was not just in music that the gardens featured. They were present in the paintings of several artists from the BSR, including those of Tom Monnington and Winifred Knights. Monnington’s The Annunciation, painted over 1924 and 1925, was set in the Borghese gardens. The scene features several figures stood talking beneath the trees, with a gentle woodland set in the background. The shape of the trees, and the articulation of their branches and leaves, were almost certainly inspired by the gardens close by. The pond, and the pathways around it, similarly mirror this picturesque landscape. The gardens also served as the setting for Knights’ The Marriage at Cana. A figure who is portrayed sketching by a tree may be a reference to her own time spent in the gardens. The tall trees and woodland background, along with the serene and restful body of water, are inspired by this “gently wild” locale.

The Rome scholars undoubtedly spent much of their time relaxing in this space, soaking in the atmosphere, and enjoying a Roman scenery that, though it may well have been inspired by the landscape gardens of England, was unavailable to them back home.

Where would you like to go next? Who would you like to meet?

Sources and Further Reading

The Marriage at Cana (1923) by Winifred Knights. Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/39515.

Hawthorne, N. (1860). The Marble Faun.

Wikipedia – Villa Borghese gardens

For a full bibliography and further reading, see here.